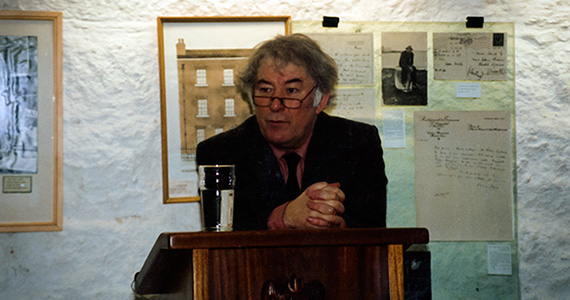

Seamus Heaney stands with ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į students and Professor Peter Balakian (far right) in Martello Tower just south of Dublin in 1993.

EditorŌĆÖs Note: Peter Balakian is director of creative writing at ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į where he has been a member of the faculty since 1980.

I first learned of Seamus HeaneyŌĆÖs death on Friday morning August 30, quite early, when I opened my computer to find an email from a former student. I was not fully awake and didnŌĆÖt first trust the subject line of the email. Then I opened it and read the short piece on HeaneyŌĆÖs death at 74. By the end of the day I would received numerous emails from former students remembering the time they had spent with Heaney on the Irish leg of the London Study Groups they took with me in 1988 and 1993. As the day went on the coverage of SeamusŌĆÖs death grew and grew until by Saturday morning it was the lead story on the front page of the New York Times.

I note that it was lead story because great and or famous writers sometimes get a front page story in the Times, but itŌĆÖs usually at the bottom of the front page. The tribute to Heaney was in my memory unprecedented. He was one of the most important poets of the twentieth century and a literary critic of an uncanny kind, a Nobel laureate, and a great deal has been written about his work. But, he was also a teacher of exceptional gifts and he reached many people in ways that strike me as unusual, especially for most writers at his level of public life and international (I wonŌĆÖt use the word celebrity because he would disdain it) acclaim. His generosity and attentiveness to others, his interest in human interaction, and his charming way of embracing an occasion were unusual. The emails I received from studentsŌĆöstudents I hadnŌĆÖt heard from in yearsŌĆöwere a reminder of that. I wrote the following for the ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į Scene after Seamus had received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters here in 1994.

Essay from the ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į Scene, July 1994:

I woke early in a small dark room at the Ormond Hotel, a slightly seedy refurbished nineteenth century place that overlooked the Liffey, a brownish river that morning with a little turbulence as it flowed through the city. The OrmondŌĆÖs claim to literary history came from James JoyceŌĆÖs depiction of it in Ulysses. It was a damp, cool, mid-October morning, and the sky was just turning from black to gray as I opened the curtains. I had arrived with my ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į study group students the night before to begin a five day tour of Ireland as part of my seminar on Yeats. When I called Seamus from the Ormond in the early evening to let him know we had arrived (no cell phones from airport in those days), he said before we hung up, ŌĆ£call me as early as you want if it helps ease the jitters, I know how much it takes to lead this kind of project.ŌĆØ I called the Heaney house at about 7 a.m. forgetting, I fear, how early it was. Seamus answered as if heŌĆÖd been up for hours and assured me he would meet us at 9 in Martello Tower in Dun Laogharie, a few miles south of Dublin and another place Joyce had memorialized in Ulysses.

Seamus had been essential to my making the whole Yeats trip to Ireland possible. We had spent sessions over dinner and a few beer sessions as well in Cambridge in the spring plotting it out. It was SeamusŌĆÖ map of YeatsŌĆÖs Ireland geared for four days with a troupe of students: necessary spots in Dublin and the landscapes and essential places in Sligo and Galway. When I learned upon arriving in Galway that that Thor Ballylee, YeatsŌĆÖs famous tower-home was closed for the season, I called Seamus in Dublin and he said, ŌĆ£DonŌĆÖtŌĆÖ worry, IŌĆÖll make a call.ŌĆØ His eleventh hour phone call to the Irish Tourist Board in Galway got the tower open for us, and my students who were particularly focused, I would say, even obsessed with walking to the top of that Norman tower rejoiced and were in further awe of HeaneyŌĆÖs powers.

Two days earlier the students sat in a round stone-walled room in Martello Tower surrounded by artifacts of James Joyce and Oliver St. John Gogarty (JoyceŌĆÖs friend and the source for Buck Mulligan in Ulysses). Out the window we could see the silvery light on Dublin Bay and then at 9 sharp Seamus appeared hobbling up the stone steps and in considerable pain, as he told us he had stepped wrong in a drop off on the sidewalk and twisted his knee badly enough so that he gave off a wince of pain now and then all morning. He was wearing a tie and a tweed jacket and talking with a kind of eloquence and often brilliance that marked his particular style of lecture/ talk/rumination. I had heard Seamus give public lectures before but the students hadnŌĆÖt, and they were not only engaged but moved and excited. It was gratifying to look around the room and watch them as Seamus meditated on the cultural circumstances of YeatsŌĆÖs work, the formation of his language, and some of YeatsŌĆÖs great poems like ŌĆ£Meditation in Time of Civil WarŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Under Ben Bulben.ŌĆØ Some good conversation generated by the students followed, and then there was some book signing. The students then went off to a few local pubs and Seamus and I had a chance to talk over beer and lunch at a small restaurant in Dun Laogherie before our tour bus came for Sligo.

It was the first time Seamus Heaney had met with ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į students at JoyceŌĆÖs Tower (he would meet with Michael CoyleŌĆÖs group later in the ŌĆś90s), but not the first time he had met with our students. Bruce Berlind, poet, translator and Charles A. Dana professor of English emeritus had brought Seamus to read his poems to London study groups in the late ŌĆÖ60s and mid ŌĆś70s as did Terrence Des Pres in the early ŌĆś80s. And, Terrence Des Pres (distinguished literary critic) and I brought Seamus to ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į in 1984 to read to a packed Brehmer Theater. But what happened in Martello Tower was an encounter of another kind. Of course the class was situated in a mythic literary place, but it was also a conversation that happened in the open-spaced arena of a seminar ŌĆö a round-walled room in this case ŌĆö in which students and writer spent time for a while, had serious conversation and lingered to keep talking after books were signed. If we hadnŌĆÖt been on a bus-driven schedule to get to Sligo and if SeamusŌĆÖs knee werenŌĆÖt banged up, we would have lingered even longer.

MORE

In his commencement talk to the Class of ŌĆÖ94, ŌĆ£Faith, Hope, and Poetry,ŌĆØ Seamus said:

ŌĆ£Faith, hope, and poetry are all manifestations of creative mind, that uniquely human gift for outstripping the negative evidence with a positive impulse, a gift held in special trust by those privileged to receive a liberal education at a university like ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į. The mind where faith, hope and poetry are grounded is not a tabula rasa, not a blank to be dedicated to and overwritten by experience; it is rather a trampoline where the dream of whatŌĆÖs possible flexes and springs back off the given circumstances. Faith, hope, and poetry have more to do with the mindŌĆÖs come-backs than with its concessions. They have to do with what used to be called the angelic in our make-up, and the function of the angelic was always to act as a go-between, to keep the lines open between the natural and the supernatural realms. The angel of faith, the angel of hope, the angel of poetry are messengers arriving to remind us of the reality of an extra dimension that the human thing inside us believes in, trust in and wants to have expressed.ŌĆØ

When I think of why it matters to bring writers to campus ( IŌĆÖm focusing on writers here, but I donŌĆÖt meant to exclude other creative artists or scholars), but writersŌĆö in this case for a the particular things writers do, I think of what Seamus made happen in Martello Tower for my students those mornings in Dublin and in the small classes in London or in Brehmer Theater where he also read to us. Many writers make extraordinary things happen in their encounters with students. The Living Writers Series that is directed by professors Jane Pinchin and Jennifer Brice, or the poetry series that I direct in the spring semesters, continue versions of the Martello Tower effect. That often dynamic interaction between readers and students of literature and those who make itŌĆö can have a legacy for students that lasts long after they have graduated.

IŌĆÖm recalling this scene from graduation weekend of 1994. After a long day of social engagements, a party at our house for Seamus and his wife Marie, a dinner with President Grabois, trustees and other honorary degree recipients, and other social encounters, I told Seamus and Marie that they didnŌĆÖt have to attend the torchlight ceremony in which the seniors march with lit torches in handŌĆöall 700 or so of them around Taylor Lake and up the hill to the Chapel. Seamus was adamant: he and Marie wanted to see this legendary, slightly tribal ║¼ą▀▓▌┤½├Į ceremony. So Helen and I took Seamus and Marie over to Broad Street and stood until the dark came and the torch flames were lit. Slowly students processed around the lake and up the hill, and after a good while I turned to Seamus and said, ŌĆ£youŌĆÖve had a long day, and weŌĆÖre happy to take you back to the hotel whenever you want. ŌĆ£ Seamus smiled and replied, ŌĆ£I want to stay till the last student passes so I can feel part of the Class of ŌĆÖ94.ŌĆØ